Decentralisation and MiCAR

The Monero Policy Working Group (MPWG) is a loose quorum of individuals attempting to engage in regulatory and policy conversations regarding cryptocurrency, blockchain and distributed ledger technologies.

Introduction

In a previous post, published on reddit and the Monero Policy Working Group website, I outlined the impact of the European Market in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCAR) on the Monero ecosystem.

In that post, I detailed that ‘fully decentralised’ crypto-asset offerings (activities, products, or services), without any intermediary, were exempt from the regulation. Seems like a win for decentralised projects? The issue is that that the term ‘fully decentralised’ has not been clearly defined, casting doubt on how to interpret and apply the regulation.

To complicate matters, the regulation states “…when part of such activities or services is performed in a decentralised manner” (MiCAR, Recital 22) – they are bound by the regulation.

This blog will attempt to provide some clarity as to what ‘fully decentralised’ might mean, shedding light on how ‘decentralised financial services’ (otherwise known as DeFi) that exist within the wider Monero ecosystem might be impacted by MiCAR.

Please note that what is written here is not legal advice. It is just a blog.

Also, it is worth remembering that providers of non-custodial hardware and software wallets are exempt from being classified as crypto-asset service providers, and thus exempt from the regulation (MiCAR, Recital 83).

MiCAR focus

As I pointed out in the first blog, MiCAR sets rules for the European Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) ecosystem, providing legal obligations (MiCAR, Article 2) for aspects related to:

- transparency and disclosure requirements for the issuance or offer to trading of crypto-assets; requirements for the authorisation, supervision, operation, organisation and governance of crypto-asset service providers, and issuers of tokens;

- requirements for the protection of holders of crypto-assets;

- requirements for the protection of clients of crypto-asset service providers;

- measures to prevent insider dealing, unlawful disclosure of inside information and market manipulation related to crypto-assets.

MiCAR and decentralisation

While the general scope of MiCAR is probably beneficial for overall consumer acceptance and stability of the DLT ecosystem, the wording around the concept of ‘decentralisation’ is less so. With that in mind, what exactly is the wording? The answer is found in Recital 22:

(22) This Regulation should apply to natural and legal persons and certain other undertakings and to the crypto-asset services and activities performed, provided or controlled, directly or indirectly, by them, including when part of such activities or services is performed in a decentralised manner. Where crypto-asset services are provided in a fully decentralised manner without any intermediary, they should not fall within the scope of this Regulation. This Regulation covers the rights and obligations of issuers of crypto-assets, offerers, persons seeking admission to trading of crypto-assets and crypto-asset service providers. Where crypto-assets have no identifiable issuer, they should not fall within the scope of Title II, III or IV of this Regulation. Crypto-asset service providers providing services in respect of such crypto-assets should, however, be covered by this Regulation.

MiCAR (unfortunately) does not explicitly describe, or indicate, how to determine whether a service or activity is “…provided in a fully decentralised manner without any intermediary”.

The immediate suggestion might be to try and identify an intermediary – if one is found, then MiCAR applies. If one isn’t, then it doesn’t. Seems simple enough, right?

In reality – without a definition of ‘intermediary’ (there is none in MiCAR) - this might be viewed as a risky approach.

The text of the regulation (MiCAR, Article 142, 2(a)) states that a report is due by late 2024:

- (a) an assessment of the development of decentralised-finance in markets in crypto-assets and of the appropriate regulatory treatment of decentralised crypto-asset systems without an issuer or crypto-asset service provider, including an assessment of the necessity and feasibility of regulating decentralised finance;

It is worth noting that the text cited above creates an explicit relationship between “decentralised crypto-asset systems” and “decentralised-finance” (with or without the hyphen).

Decentralised crypto-asset systems and decentralised finance (DeFi) are inextricably linked, and (one might assume) almost interchangeable concepts. There is probably a lot more nuance to this claim but, for simplicities sake, let’s treat the two two terms as interchangeable.

The “assessment” obliged by Article 142(2)(a) has now been delivered. It is jointly authored by the European Security and Markets Agency (ESMA) and the European Banking Authority (EBA), and titled “Recent developments in crypto-assets (Article 142 of MiCAR)”. It is available here.

The primary focus is on decentralised finance (DeFi) and, in particular, topics such as:

- Consumer protection;

- ICT risk and risk mitigation;

- Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) and systemic risks related to that concept;

- Lending and borrowing, and staking.

Decentralisation, as a concept, is covered only broadly. It does not provide guidance on how to determine what ‘fully decentralised’ means exactly.

The report does, however, explicitly state that European regulatory bodies (and national competent authorities) should continue to work with global authorities, such as the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), to determine when an entity should be considered a Crypto-Asset Service Provider (CASP) – and therefore an obliged entity (ESMA Report, Paragraph 97, pp.25-26).

As the report does not provide any real clarity on the ‘decentralisation exemption’, we have to look elsewhere.

The question of ‘decentralisation’ is particularly relevant for determining how decentralised finance (DeFi) might develop in Europe, and also how Decentralised Exchanges (DEXs) – including those that provide services for Monero – will determine their regulatory exemption (or liability).

Ultimately, the difference between being classified as ‘fully’ or ‘partly’ decentralised will determine both compliance obligations and, more importantly, apportioning of legal liability.

So, what exactly is decentralisation then?

You might be surprised how difficult this question is to answer.

We all have a vague idea of what decentralisation might mean (e.g., no single governing entity, no centralised authority, no single coordinating entity, etc), but pinning it down to a formal definition is pretty difficult.

It gets further complicated when attempting to decide what indicator should be used to determine when something is ‘decentralised’ or ‘centralised’, or whether there is some threshold that, when crossed, determines if something is ‘no longer decentralised’.

In reality, ‘decentralisation’ is a spectrum: with a range between ‘fully decentralised’ and ‘not decentralised at all’.

However, these terms are pretty vague and finding some indicator in order to place a target on the spectrum, seems an illusive goal.

Academic research on decentralisation

There is a rich tapestry of research on the concept of decentralisation, predominately studied through frames such as network theory, management theory, behavioural theory, and political theory (to name a few).

An article authored by Bodó, Brekke, and Hoepman, in 2021 and, incidently, funded by the European Research Council provides a ‘multidisciplinary’ overview of the topic.

Bodó et al, understand ‘decentralisation’ through the lens of network theory. Following on from the seminal (but often criticised) work of Paul Baran, published in 1964. Decentralisation is framed as the ‘level of node distribution in a network’, with a range existing between ‘centralised’ and ‘radically decentralised’, or, alternatively,‘distributed’.

In network theory, years of research built on the early work of Baron. For example, the book entitled Network Science, by Barabási delves into concepts related to emergence, resilience, and network evolution.

Bodó et al, however, maintain their focus on DLT networks and, critically, distinguish between three types of decentralisation discourse (Bodó et al, 2021):

- Design-based: decentralisation is a principle for design and engineering which can be used as a means to achieve certain properties.

- Aim-based: decentralisation can be an aim, where a given system is intended to have decentralising effects, for example decentralising the load of computation.

- Claim-based: decentralisation can be a claim, whereby a given system is designated as a decentralised system, but does not always live up to that in its deployment.

A small sub-section of decentralisation research (though growing) explicitly focuses on cryptocurrency ecosystems. A paper, entitled Deconstructing ‘Decentralization’: Exploring the Core Claim of Crypto Systems, written by Angela Walch describes how ‘decentralisation’ is being used in myriad (often confusing) ways. She references how the term is impacted by, and impacts on, the concept of ‘permissionless’, noting that the two concepts seem inextricably linked, and requiring of mutual inclusivity.

Walch also explains how ‘decentralisation’ is being used as ‘a claim’ which, ultimately, determines legal liability. This is relevant for regulatory authorities, such as the United States Securities and Exchanges Committee (SEC), whose historic role was to determine whether DLT tokens are designated securities, or not. Their role is evolving in the current political climate, admittedly, but in the recent past their role was designated as this arbiter.

Walch describes this in her introduction, acknowledging the legal ramifications of ‘claim-based’ decisions. Walch builds on work by Marcella Atzori, effervescently stating:

“To be fully decentralized (whatever that means) is viewed as one of the ultimate goals of a permissionless blockchain system, a utopian summit to be scaled” (Walch, 2019, p. 6).

Walch also points to Vitalik Buterin, Sarah James Lewis, on Twitter/X, and Nic Carter’s MSc Thesis to support the broad perspective that decentralisation is: a) complicated, b) difficult to define, and c) often impossible to quantify accurately.

She explains how the concept is further muddied if you consider networks as consisting of layers, all of which are required to be ‘decentralised’ if we can apply the term ‘fully decentralised’ in any meaningful way.

Vitalik Buterin addressed the topic in 2017, describing the tripartite nature of the discourse. He outlined three spectrums (including US Spelling):

- Architectural (de)centralization: how many physical computers is a system made up of? How many of those computers can it tolerate breaking down at any single time;

- Political (de)centralization: how many individuals or organizations ultimately control the computers that the system is made up of?;

- Logical (de)centralization: does the interface and data structures that the system presents and maintains look more like a single monolithic object, or an amorphous swarm? One simple heuristic is: if you cut the system in half, including both providers and users, will both halves continue to fully operate as independent units?

Buterin discredits the original diagram of Paul Baran – especially the manner in which it has been parroted across domains in sometimes confusing, or inaccurate, ways. Buterin does not, however, provide any meaningful way to qualify or quantify decentralisation in practice.

It is easy (and endless) to pitter patter around decentralisation philosophy – but, ultimately, what matters (especially with respect to legal liability) is how regulators understand, and apply, the term.

The ‘authorities’ on decentralisation

Regulatory speaking, there are a few ‘official positions’ available on the topic.

Notable international and European agencies such as the OECD, the BIS, Banque de France, ESMA, and the ESRB have all provided their ‘expert reports’ on DeFi. None, however, have provided a robust definition, or methods, for determining the degree of decentralisation.

Does decentralisation exist?

A common theme does emerge when reading the reports: they believe that decentralisation in the DLT ecosystem is often ‘claim-based’.

They believe that projects, and networks, often publicly signal they are decentralised but, when analysed, it is usually possible to identify a centralised layer. This might be a concentration of decision making rights, a concentration of power in the validating nodes/miners, or a concentration of power over commits to a codebase. Usually this centralisation is kept somewhat opaque, in the broad hope that the market, or regulatory authorities, don’t dig deep enough to uncover it.

This line of thinking is not entirely new. Trail of Bits (a DLT security and consultancy firm) provided their perspective on DLT decentralisation when engaging with DARPA sometime before 2022. Their opinion is that centralising forces exist across several DLT spectrums. It would seem, unfortunately, that these forces can be extrapolated (for the most part) to DLT-focused products and services (including the provision of DEX services).

In a similar vein, the BIS talk of a ‘decentralisation illusion’, taking a completely dismissive stance of the existence of decentralisation:

“…the need for governance makes some level of centralisation inevitable and structural aspects of the system lead to a concentration of power.” (BIS, p.1)

Banque de France dismisses decentralisation as a concept, and classifies the majority of DeFi projects as ‘disintermediated’ (Banque de France, Box.1, p.8), while the ESRB, supported by the aforementioned research from the BIS) claim strongly:

While it is possible to see a pattern of thought emerging, the OECD take a more considered approach. They describe three core characteristics of DeFi projects:

- Non-custodial: No central authority or other intermediary gains access to or control over participants’ digital assets;

- Self-governed and community driven: DeFi protocols are open-source and allow the community to review and further develop the code underlying the protocols (the OECD, however, note that many DeFi projects do not allow their community to vote, have voting disconnected from governance tokens, or do not allow protocol changes through voting mechanisms);

- Composable: Existing components of DeFi networks (i.e., digital assets, smart contracts, protocols and applications built on top of the protocol layer) can be combined to create new applications. The open source nature of DeFi applications is a critical enabler of this attribute, as it allows everyone to look at the code and use it to create new applications.

The Danish Financial Supervisory Authority (otherwise known as Finanstilsynet) also provides a more considered (though nuanced) perspective, mirroring some of the work from the OECD.

Finanstilsynet are the designated National Competent Authority for Denmark, responsible for implementation and oversight of MiCAR in Denmark.

They recently published “Principles for the assessment of decentralisation in the markets for crypto-assets”.

The report provides a broad discussion of the concept of decentralisation and, correctly, outlines that the regulation (MiCA):

“…does not address when a service can be regarded as being offered in a fully decentralised manner. MiCA or other legal acts also do not contain a clear definition of the concept of ‘decentralised’. It is thus a new concept.” (Danish Financial Supervisory Authority, p.5)

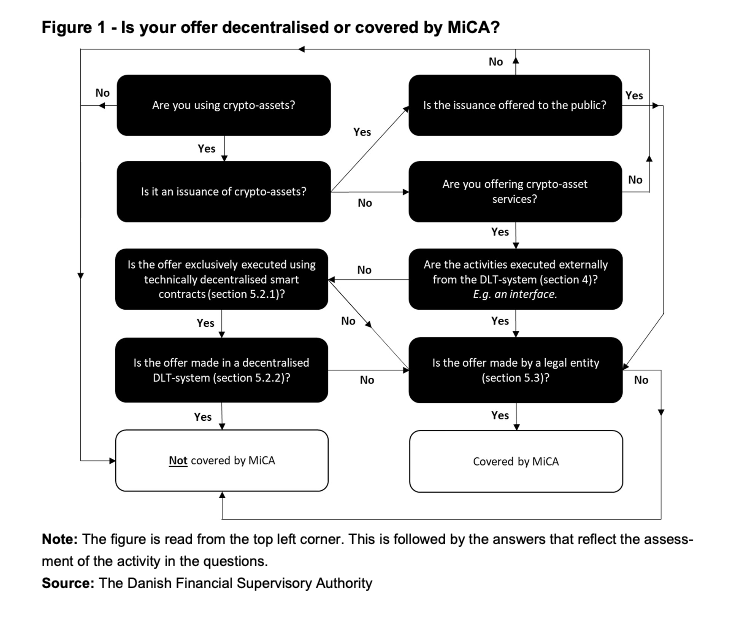

Finanstilsynet, however, do provide a method for qualifying the degree of decentralisation. The method is based on a series of questions of which ‘yes/no’ responses determine whether a product, service, or activity is bound by MiCAR.

The high-level overview is provided in this diagram:

Finanstilsynet put great emphasis on the existence of a ‘legal entity’, including the ability to identify the specific activity that the legal entity has disposal over.

The existence of a legal entity that enters into a provision of software, execution of contract, or interaction (including an interface – whether application or web-based) is a critical determinant of whether the offering is ‘fully’ or ‘partially’ decentralised.

This has ramifications for how ‘fully decentralised’ products, services, or activities should be presented to the market.

In reality – they should follow the core characteristics outlined by the OECD, and, correspondingly, ensure that no legal entity has singular disposal over meaningful components of the offering. Practically, however, this might be more difficult than it seems.

As outlined in the Finanstilsynet report, applications offered on app-stores owned by Apple or Google require a legal entity for authentication and accountability purposes.

The infrastructure that supports DeFi offerings will, more than likely, require third-party services to run correctly (servers, domain name registrations, website hosting services, etc).

These will probably have to be purchased, or rented, by a named entity (legal or natural person). All of these might provide an explicit avenue of implication under the ‘all perceiving eyes’ of the regulator.

It’s also important to note that we have seen recent judicial rulings, such as the CFTC vs Ookie DAO, that implicates a ‘group of participants’ as ‘partnerships’, which in turn has legal ramifications.

This attack surface is seemingly accounted for within MiCAR: “(22) This Regulation should apply to natural and legal persons and certain other undertakings…” (MiCAR, Recital 22)

Whether or not we will see similar rulings in European courts is still unknown. The United Kingdom Law Reform Commission recently published a paper on DAOs and their legal ramifications, while the European Central Bank published a paper on DAOs and their future in finance.

Both papers seem to pose more questions than answers, but suggest that the existence of a DAO does not immediately imply lack of legal liability – individually or collectively.

Whether this line of thinking can be extrapolated to “…certain other undertakings…” (MiCAR, Recital 22) such as loose communities of people, repository contributors, repository maintainers, network participants, etc, is still extremely opaque.

This might not be the most welcome conclusion but, unfortunately, with the nascent state of decentralised systems, this is where we are.

It is difficult to imagine a world where ‘decentralisation == exemption from legal liability’, but it is also difficult to imagine a world where the decentralisation ideology isn’t able to lead the development of meaningful, and impactful, tools for the beneficial development of society.

Conclusion

In the murky, muddy, and distinctly dirty world of DL Techno-infused-enfranchisement, decentralisation might be viewed as a ‘pseudo-fantasia’. Much like the word ‘blockchain’, we have reached a stage of apoplectic semantic satiation. It means everything and nothing simultaneously.

Decentralisation is parroted as the panacea for humanities ills, leveraged on web3, and driven by a desire to build everything on a rich bed of proto-meme-monetarianism and cryptographic allegory, served alongside some sort of verifiable packed lunch (with a side of cheese strings).

In reality – the Rule of Law wants to eat the Law of Code for breakfast. This process is both financially lucrative and era-defining; mixed together with a pinch of salt in the zeitgeist’s technocratic political power stew.

What more could technologists, angel investors, lawyers, policy makers, and regulators want to massage their emboldened egos?

Practically speaking – it’s going to be extremely difficult to prove, conclusively, that a DLT offering is ‘fully decentralised’ – but that doesn’t mean it’s not worth trying, even if the baying hound of the regulator is at the door.

Ensuring crypto-asset offerings are completely free and open-source, permissionless, and explicitly community driven (including software distribution, code maintenance, idea collation, and governance) seems a fair starting point.

Removing identifiable profit motives, revenue streams, and any, and all, legal entities from the socio-political tech stack seems the next logical step.

After that? Probably urge others to build on what has been built – fostering emergence and driving explicit bifurcation across both physical, and digital, planes.

Is all that actually achievable and sustainable? Honestly, I have no idea. Thankfully, the regulators probably don’t know either.

The Monero Policy Working Group (MPWG) is responsible for this content. This is not legal advice, and it should not be relied upon for any purpose by third parties. To learn more about the MPWG, click here.

This authorship of this blog was kindly supported by funding from Power Up Privacy.